Somatic Psychology, Contemplative Practice, & Affective Neuroscience

For most people, bodywork is about working on bodies, and muscles in particular. And this is a peculiar thing, because if one asks the same people what their main reason for getting a massage is, the #1 answer is to relax or reduce stress, and their #2 answer is to relieve pain. Relaxation, or stress reduction, is much more about the mind than it is the body, and while pain is a very complex topic, it, too, is also much more about the nervous system than it is about muscles.

Clearly bodywork has relevance far beyond the body and bleeds over into the realm of psychology whether it wants to or not. In many bodywork sessions, clients find that emotions arise during the session that don’t normally arise outside of a bodywork session, and most clients leave a session with a feeling that isn’t fully captured by the word ‘relaxed’ but more often is better captured by a word such as ‘aliveness’ or ’embodiment’. At PCAB, we think the feeling of aliveness or embodiment is a good thing to have more of.

Ultimately, massage is being undersold when it’s thought of only in terms of muscles, because touch is an extremely powerful thing for humans, and all mammals–far more powerful than smell, taste, sight, or hearing. For instance, human infants will die without touch, even if their food and water needs are met, and the amount of early neural development is directly related to how much touch is received beyond the minimum required for feeding. Touch plays a huge role in the short and long-term health of premature infants, and the amount of and type of touch received during childhood sets the stage for an entire lifetime of physical and mental health conditions, the understanding of which is very much the realm of psychotherapy and psychoneuroimmunology.

There are many branches on the psychotherapy tree. One of those branches is somatic psychotherapy, which contends that the mind and body are not separable and that to understand thoughts, feelings, and behavior, one must understand the body’s inextricable role in these phenomena. How do the body and mind affect one another? Why does one person panic in a situation where another does not, and what kind of touch has what kinds of effects, and why? What does it mean to feel good or feel happy, and what gets in the way of this? These are all questions within the three realms of somatic psychology, affective neuroscience, and contemplative practice.

At PCAB, we integrate insights from these three realms into our massage therapy program for a number of reasons. First, while one can be an effective massage therapist without this integration, the depth of appreciation for what is happening beneath our fingertips becomes far more profound with this integration. Second, integrating the insights and skills from these fields makes a massage therapist a better human being and (therefore) a better massage therapist. Third, if a massage therapist doesn’t understand how emotions work and why they come up, s/he cannot optimally work with a client who is having emotions arise during a session. Lastly, the additional insights allow the therapist to provide the client with a much more powerful experience while still remaining within the massage therapy scope of practice.

The Practitioner Cultivation and Relational Skills training at PCAB is an experiential co-exploration of psychology and communication that consists of a diverse blend of principles and techniques gleaned from somatic psychology, humanistic/transpersonal psychology, affective neuroscience, and vipassana/mindfulness meditation. Common themes that run through this portion of the course include direct experience of bodily sensations (interoception), presence of aware being, and the opportunity of living from these in the present moment. All methods are non-judgmental, non-directive, non-regressive, client-centered, client-empowering, and client-resourcing. In addition, while our approach is non-regressive (not diving into the past), by rooting in present experience we also very intentionally avoid promoting spiritual bypass, which is an all-too-common psychologically-dissociative practice that readily emerges within all religious and healing traditions of using spiritual beliefs, good feelings, pretty symbols, and “nice” language to avoid deeper pains and wounds.

We integrate components of these techniques into the entire program with the intent of developing relational skills as a massage therapist. Many derive great personal benefit from these techniques as a client and report that this was the most valuable part of the program for them. These personal benefits makes one a better listener, which will make one a better massage therapy practitioner and is useful for creating more peace and ease in any relationship, whether it’s with family, partners, children, friends, colleagues, co-workers, strangers….or yourself.

The first set of tools that we emphasize are focused on the personal level, which concerns the significant events of one’s life, one’s emotional relationship to those events, one’s beliefs and attitudes, and the behavioral and cognitive patterns that one has developed in an attempt to bring about the most wellbeing for oneself. For many, this level involves unexpressed, and therefore unresolved, traumas, as well as beliefs about ourselves. PCAB offers a unique setting that’s safe enough to allow for true exploration. We endeavor to co-create a safe space to allow for the significant events to be expressed while also getting to the heart of the matter.

Secondly, we add interpersonal tools, such as NVC, to focus on the development of communication skills to help with enhancing compassion in social contexts. These tools assist both in helping to enhance a compassionate approach towards others and in altering speech patterns so that they are less likely to create defensiveness and more likely to create empathy in the listener and harmony in the relationship.

Lastly, we move our attention towards the transpersonal level, to bring awareness towards the part of oneself that is okay with whatever is present, including one’s own emotional responses of fear, anger, or anxiety, as well as pleasantness, joy, and love. At this level, our personal story and our interpersonal struggles lose their grip, revealing a place of deep stillness, clarity, and/or vibrant aliveness.

While none of these valuable techniques are necessary for acquiring a massage therapy license, we teach them and integrate them throughout the entire program because we believe that their use makes for more effective bodyworkers and, more importantly, more compassionate and joyful people who can more fully experience their own aliveness and authenticity.

See also our page on Trauma-informed bodywork.

Somatic Psychology History

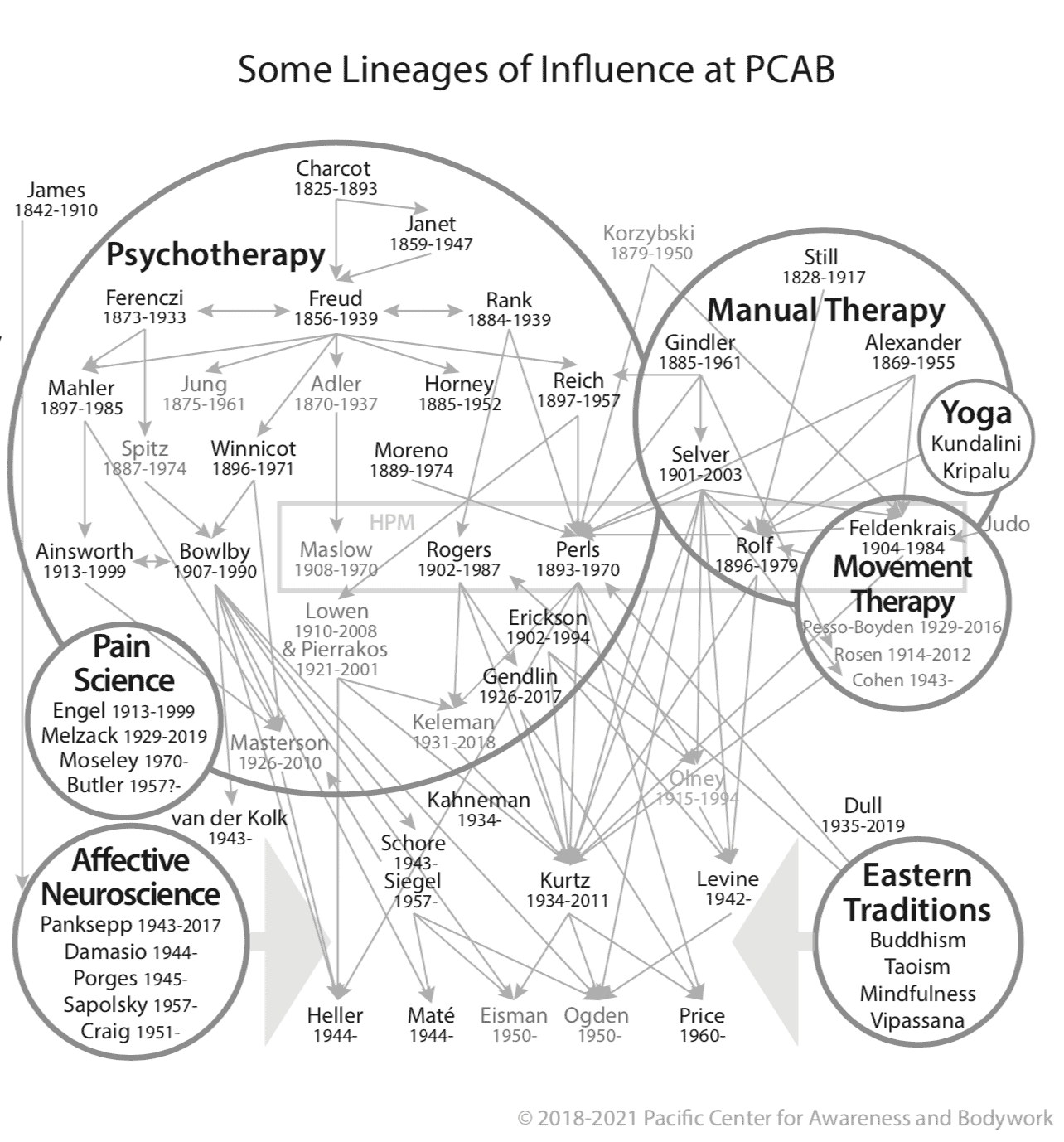

Somatic Psychology is generally thought to have its beginnings with Freud, or his student Wilhelm Reich. See the graphic below for an overview of the most well-known individuals and approaches over the last century that have varying levels of relevance to our massage therapy program.

-

Somatic psychology is an interdisciplinary field involving the study of the body, somatic experience, and the embodied self, including therapeutic and holistic approaches to the body. Its history extends over a hundred years back to Wilheim Reich, and its ideas align well with recent affective neuroscience research on emotions/feelings, memory, personality, attention, and consciousness.

-

Humanistic psychology emerged as a third wing of psychology in contrast to Freudian Psychotherapy and Behaviorism. Humanistic Psychology includes several approaches to counseling and therapy. Among the earliest approaches we find the developmental theory of Abraham Maslow, emphasizing a hierarchy of needs and motivations, as well as the work of Carl Rogers. Both Maslow and Rogers were part of the Human Potential Movement.

-

Affective Neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience that is focused on the basis for emotions (aka affect), personality, and the multidirectional relationships between cognition, emotion, and body physiology. Regions of the brain most often studied in Affective Neuroscience include limbic structures (e.g. hippocampus, amygdala, hypothalamus, cingulate, insula, orbital frontal cortex, ventral striatum, and the ventral medial prefrontal cortex).

-

Wilheim Reich was a psychoanalyst who, among other things, integrated massage into this psychotherapy practice, much to the dismay of his colleagues. Reich was a student of Freud’s and is generally considered the father of somatic psychology.

-

Gestalt therapy puts a focus on the here and now, especially as an opportunity to look past any preconceived notions and focus on how the present is affected by the past. Role playing also plays a large role in Gestalt therapy and allows for a true expression of feelings that may not have been shared in other circumstances. In Gestalt therapy, non-verbal cues are an important indicator of how the client may actually be feeling, despite the feelings expressed. Gestalt was developed by Fritz Perls, a student of Reich’s. Perls was part of the Human Potential Movement and was influenced by the Alexander Technique as well as Ida Rolf, the founder of Structural Integration.

-

The NeuroAffective Relational Model (NARM) was developed by Dr. Larry Heller to specifically work with developmental and complex trauma, as opposed to shock trauma, which SE is designed for. NARM’s focus on developmental trauma makes it unique among the somatic therapies, most of which were developed before the relatively new concept of developmental trauma was outlined.

-

Somatic Experiencing (SE) is based on the understanding that symptoms of shock trauma are the result of a dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and that the ANS has an inherent capacity to self-regulate that is undermined by trauma. SE bases its approach on the science that mammals automatically regulate survival responses from the primitive, non-verbal brain, mediated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS). In the wild animals spontaneously “discharge” this excess energy once safe. Involuntary movements such as shaking, trembling, and deep spontaneous breaths reset the ANS and restore equilibrium. Humans disrupt this discharge through our enculturation, rational thinking, shame, judgments, and fear of our bodily sensations. Somatic Experiencing (SE) approach works towards restoring this inherent capacity to self-regulate by facilitating the release of energy and natural survival reactions stored during a traumatic event. Sessions are normally done face-to-face, and involve a client tracking his or her own felt-sense experience.

-

Interpersonal Neurobiology (IPNB) is essentially an interdisciplinary field which brings together many areas in science including but not limited to anthropology, biology, linguistics, neuroscience, and psychology to determine common findings about the human experience from different perspectives. At its core, interpersonal neurobiology holds that we are ultimately who we are because of our relationships. Further, because the mind is defined as a relational process that regulates energy flow, our brains are constantly rewiring themselves. All relationships–particularly the most intimate ones with our primary care givers or romantic partners–change the brain. While it was once thought that our early experiences defined who we are, interpersonal neurobiology holds that our brains are constantly being reshaped by new relationships. A short-term dose of effective couples therapy, namely Emotionally Focused Therapy, can change the way the brain responds to fear and threat. This is but one of many neuroimaging studies that demonstrate how the brain can change over time based on relationships and new experiences. We are more social than we realize. Social pain is coded similarly in the brain as physical pain: Both forms of pain signal danger to our survival. Interpersonal neurobiology adds to the growing body of research that demonstrates just how social of an animal we are.

-

The Hakomi Method is a form of mindfulness-centered somatic psychotherapy developed by Ron Kurtz in the 1970s. Hakomi uniquely relies almost entirely on mindfulness of body sensations, emotions, and memories during the entire therapy session, and the goal is to transform core beliefs. Each session follows an arc starting with building rapport and establishing mindfulness, then evoking experience through “experiments in mindfulness”, followed by processing, transformation, and integration.

-

Integrative Body Psychotherapy (IBP) is a psychotherapy that is based on the premise that the body, mind, and spirit are not separate, but rather integrated parts of a whole person. IBP is a synthesis and implementation of numerous therapies, including Attachment Theory, Gestalt therapy, Transpersonal therapy, Alexander technique, and Feldenkrais bodywork. One of the key concepts of IBP is that early childhood stresses are held in the body as blocks that are exhibited as chronic muscular tension, organ dysfunction, and/or lack of sensation. A key component of IBP treatment is to facilitate the release of the blocks through physical exercises, physical and emotional release, and psychological processing.

-

Eriksonian hypnosis is a particular kind of hypnosis that involves metaphor, storytelling, and indirect suggestion, in contrast to the direction suggestion variety that is most often associated with hypnosis in western culture. Erikson was a prominent psychotherapist and is generally considered the father of clinical hypnosis.

-

Focusing is a process outlined by Eugene Gendlin in the mid-1950s that involves the client focusing on their internal felt-sense in order to explore their implicitly-held knowledge.

-

Vipassana meditation, also known as insight meditation, involves the observation of body sensations without striving to maintain or change them. The effect is not one of calming the mind but rather a retraining of the mind, perhaps by rewiring circuits that are involved in habitually moving towards desired states and moving away from undesired states. Research on vipassana has shown significant anatomical changes in the insula as well as changes in activity patterns in brain regions associated with self-concept processing. Due to its inherent somatic nature, it can often be retraumatizing and create dissociative states in individuals with significant trauma.

-

NVC is a non-somatic method of interpersonal conflict resolution that was developed by Marshall Rosenberg. One part of it (“giraffe inward” language) involves the speaker stating an observation, followed by a feeling, the relevant need being fulfilled or not fulfilled, and lastly a request of the listener (e.g. “When you came home late, I felt disappointed, because I have a need for quality time…”). “Giraffe outward” language involves listening for the unmet need in the speaker. NVC has been used to create more peace and understanding in countless situations worldwide, including very violent and volatile contexts.

-

Reflective Listening (RL) is a communication strategy that involves reconstructing what the client is thinking or feeling and reflecting it back to the client to confirm that the client has been correctly understood. RI is a specific form of active listening that arose from Carl Roger’s client-centered counseling theories. RL is a key component of Motivational Interviewing.

-

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a client-centered counseling style of eliciting changes in behavior by assisting clients to explore and resolve ambivalence. It is more goal-oriented and directive than non-directive styles. In addition to its role in psychotherapeutic contexts, it’s often used in manual therapy contexts.

-

Dr. Damasio is a Neuroscientist at USC who studies the neuroscience of interoception (bodily feelings) and the foundational role it plays in the development of the self and consciousness. Damasio formulated the somatic marker hypothesis, which details how emotions play a critical role in higher-level cognition, and his work has made him one of the most cited researchers of the 21st century. He has published many books, including The Feeling of What Happens.

-

Dr. Siegel is known as a mindfulness expert and for his work developing the field of Interpersonal Neurobiology, which is an interdisciplinary view of life experience that draws on over a dozen branches of science to create a framework for understanding our subjective and interpersonal lives. Siegel’s most recent work integrates the theories of Interpersonal Neurobiology with the theories of Mindfulness Practice and proposes that mindfulness practice is a highly developed process of both inter- and intra-personal attunement. Dr. Siegel has written many books, including The Neurobiology of “We”:

How Relationships, the Mind, and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are and Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation. -

Dr. Levine is the founder of Somatic Experiencing, which is a somatic psychotherapy practice developed for the treatment of shock trauma. Dr. Levine is the author of Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma.

-

Dr. Sapolsky is a neuroendocrinologist at Stanford and author of the books Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers and Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst.

-

Bessel van der Kolk is psychiatrist noted for his research in the area of PTSD. His work focuses on the interaction of attachment, neurobiology, and developmental aspects of trauma’s effects on people. His major publication, the New York Times bestseller The Body keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, talks about what we have learned about the ways the brain is shaped by traumatic experiences, how traumatic stress is a response of the entire organism, and how that knowledge needs be integrated into healing practices. Van der Kolk has published extensively on the effect trauma on development of mind, brain, and body. He has found connections to dissociative problems, borderline personality disorder, self-mutilation, and a wide range of other issues. Currently, he is conducting brain imaging research on how trauma can affect memory in individuals with PTSD. He is also researching how yoga and neurofeedback can be used as effective treatments for trauma.

Many prominent individuals in Somatic Psychology are not listed here. Some techniques utilized at PCAB may be similar to or may contain elements derived from the practices and people listed on this page, though what our program offers not constitute formal training in any of these.

Written by Mark Olson, Ph.D. LMT, the former director of the Pacific Center for Awareness and Bodywork.

Ready to Deepen Your Practice?

Integrate somatic psychology, affective neuroscience, and contemplative practices into your massage therapy training at PCAB. Click here to learn more about our program or schedule a call to get personalized guidance.